What Learning Actually Is – at a Concrete, Physical Level in the Brain

Learning is a positive change in long-term memory. By creating strategic connections between neurons, the brain can more easily, quickly, accurately, and reliably activate more intricate patterns of neurons. Wiring induces a "domino effect" by which entire patterns of neurons are automatically activated as a result of initially activating a much smaller number of neurons in the pattern.

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.

In order to develop a good intuitive sense of how learning can be optimized, it’s crucial to understand – at a concrete, physical level in the brain – what learning actually is.

At the most fundamental level, learning is the creation of strategic electrical wiring between neurons that improves the brain’s ability to perform a task.

When the brain thinks about objects, concepts, associations, etc., it represents these things by activating different patterns of neurons with electrical impulses.

Whenever a neuron is activated with electrical impulses, the impulses naturally travel through its outward connections to reach other neurons, potentially causing those other neurons to activate as well.

By creating strategic connections between neurons, the brain can more easily, quickly, accurately, and reliably activate more intricate patterns of neurons.

As one might expect, it is extraordinarily complicated to understand what these specific brain patterns are, how they interact, and how the brain identifies strategic ways to improve its connectivity.

However, to some extent, these are just nature’s way of implementing cognition – and the overarching cognitive processes of the brain are much better understood.

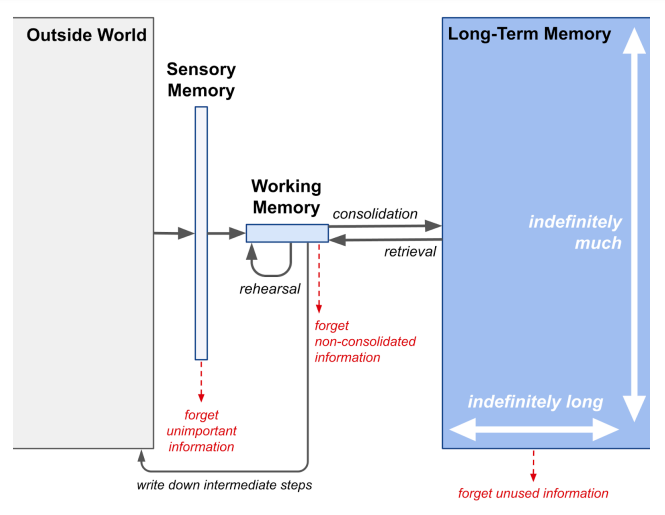

At a high level, human cognition is characterized by the flow of information across three memory banks:

- Sensory memory temporarily holds a large amount of raw data observed through the senses (sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch), only for several seconds at most, while relevant data is transferred to short-term memory for more sophisticated processing.

- Short-term memory, and more generally, working memory, has a much lower capacity than sensory memory, but it can store the information about ten times longer. Working memory consists of short-term memory along with capabilities for organizing, manipulating, and generally "working" with the information stored in short-term memory. The brain's working memory capacity represents the degree to which it can focus activation on relevant neural patterns and persistently maintain their simultaneous activation, a process known as rehearsal.

- Long-term memory effortlessly holds indefinitely many facts, experiences, concepts, and procedures, for indefinitely long, in the form of strategic electrical wiring between neurons. Wiring induces a "domino effect" by which entire patterns of neurons are automatically activated as a result of initially activating a much smaller number of neurons in the pattern. The process of storing new information in long-term memory is known as consolidation. At a cognitive level, learning can be described as a positive change in long-term memory.

These memory banks work together to form the following pipeline for processing information:

- Sensory memory receives a stimulus from the environment and passes on important details to working memory.

- Working memory holds and manipulates those details, often augmenting or substituting them with related information that was previously stored in long-term memory.

- Long-term memory curates important information as though it were writing a "reference book" for the working memory.

In the context of solving a math problem:

- Sensory memory captures visual data that lets us read the problem or any intermediate work that we’ve written down, thereby allowing the written information to be loaded into working memory. It also filters out any distractions (e.g. background noise) as we solve the problem.

- Working memory holds the relevant pieces of the problem, requests additional information from long-term memory, and applies that information to incrementally transform the pieces of the problem into the solution. The problem-solving narrative takes place within the working memory.

- Long-term memory -- upon request from working memory -- produces definitions, facts, and procedures that we learned previously. It is like an internal "reference book" that we can use to look up additional information that would be helpful while solving the current problem.

Note, however, that there is a crucial conceptual difference between long-term memory and a reference textbook: long-term memory can be forgotten. The text in a reference book remains there forever, accessible as always, regardless of whether you read it – but the representations in long-term memory gradually, over time, become harder to retrieve if they are not used, resulting in forgetting.

It’s also worth re-emphasizing that the problem-solving narrative takes place within the working memory. Sensory and long-term memory supply working memory with information, which working memory combines, transforms, and uses to guide our behavior to solve the problem.

As researchers Roth & Courtney (2007) elaborate:

- "Working memory (WM) is the active maintenance of currently relevant information so that it is available for use. A crucial component of WM is the ability to update the contents when new information becomes more relevant than previously maintained information. New information can come from different sources, including from sensory stimuli (SS) or from long-term memory (LTM).

...

In order for information in working memory to guide behavior optimally ... it must reflect the most relevant information according to the current context and goals. Since the context and the goals change frequently it is necessary to update the contents of WM selectively with the most relevant information while protecting the current contents of WM from interference by irrelevant information.

...

There are ... many ways in which WM can be changed, including through the manipulation of information being maintained (Cohen et al., 1997; D'Esposito, Postle, Ballard and Lease, 1999), the addition or removal of items being maintained (Andres, Van der Linden and Parmentier, 2004), or the replacement of one item with another (Roth, Serences, and Courtney, 2006)."

Okay… but what is working memory at a biological level?

Recall that when the brain thinks about objects, concepts, associations, etc., it represents these things by activating different patterns of neurons with electrical impulses.

Loosely speaking, the brain’s working memory capacity represents the degree to which it can focus activation on relevant neural patterns and persistently maintain their simultaneous activation.

As summarized by D’Esposito (2007):

- "...[T]he neuroscientific data presented in this paper are consistent with most or all neural populations being able to retain information that can be accessed and kept active over several seconds, via persistent neural activity in the service of goal-directed behaviour.

The observed persistent neural activity during delay tasks may reflect active rehearsal mechanisms. Active rehearsal is hypothesized to consist of the repetitive selection of relevant representations or recurrent direction of attention to those items.

...

Research thus far suggests that working memory can be viewed as neither a unitary nor a dedicated system. A network of brain regions, including the PFC [prefrontal cortex], is critical for the active maintenance of internal representations that are necessary for goal-directed behaviour. Thus, working memory is not localized to a single brain region but probably is an emergent property of the functional interactions between the PFC and the rest of the brain."

When the brain is initially learning something, the corresponding neural pattern has not been “wired up” yet, which means that the brain has to devote effort to activating each neuron in the pattern. In other words, because the dominos have not been set up yet, each one has to be toppled in a separate stroke of effort.

This imposes severe limitations on how much new information the brain can hold simultaneously in working memory via rehearsal.

Most people can only hold about 7 digits (or more generally 4 chunks of coherently grouped items) simultaneously and only for about 20 seconds (Miller, 1956; Cowan, 2001; Brown, 1958). And that assumes they aren’t needing to perform any mental manipulation of those items – if they do, then fewer items can be held due to competition for limited processing resources (Wright, 1981).

This severe limitation of the working memory when processing novel information is known as the narrow limits of change principle (Sweller, Ayres, & Kalyuga, 2011).

An intuitive analogy by which to understand the limits of working memory is to think about how your hands place a constraint on your ability to hold and manipulate physical objects.

You can probably hold your phone, wallet, keys, pencil, notebook, and water bottle all at the same time – but you can’t hold much more than that, and if you want to perform any activities like sending a text, writing in your notebook, or uncapping your water bottle, you probably need to put down several items.

In the same way, your working memory only has about 7 slots for new information, and once those slots are filled, if you want to hold more information or manipulate the information that you are already holding, you have to clear out some slots to make room.

(Note that while this “slots” analogy describes the function of working memory capacity, the underlying mechanism is more nuanced: the actual limitation is not a fixed number of neural storage units, but rather the ability to sustain relevant neural activity while suppressing interference from irrelevant neural activity. At a biological level, hitting a working memory capacity limit does not entail exhausting one’s ability to maintain more neural activity in the energy sense, but rather exhausting one’s ability to maintain focus and attention, that is, appropriate concentration or allocation of one’s neural activity.)

Long-term memory solves this problem by providing a means by which the brain can store lots of information for a long time without requiring much effort.

By creating strategic connections between neurons, the brain can more easily, quickly, accurately, and reliably activate more intricate patterns of neurons. Wiring induces a “domino effect” by which entire patterns of neurons are automatically activated as a result of initially activating a much smaller number of neurons in the pattern.

As information becomes more ingrained in long-term memory, it becomes easier to activate.

When the information becomes ingrained to the fullest extent, it can be activated automatically without conscious effort.

This is known as “automaticity”, the ability to execute low-level skills without having to devote conscious effort towards them.

Automaticity is important because it frees up limited working memory to execute multiple lower-level skills in parallel and perform higher-level reasoning about the lower-level skills.

As a familiar example, think about all the skills that a basketball player has to execute in parallel: they have to run around, dribble the basketball, and think about strategic plays, all at the same time. If they had to consciously think about the mechanics of running and dribbling, they would not be able to do both at the same time, and they would not have enough brainspace to think about strategy.

This extends to academics as well. As described by Hattie & Yates (2013, pp.53-58):

- "You cannot comprehend a 'big picture' if your mind's energies are hijacked by low-level processing. Continuity is broken. The goal shifts from understanding the total context to understanding the immediate word before you. ... If you read connected text (such as sentences) at any pace under 60 wpm, then understanding what you read becomes almost impossible.

...

Many [students] arrive at school with a lack of automaticity within their basic sound-symbol functioning. With a minimal level of phonics training, they may be able to fully identify letters, verbalise sound symbol relationships, and read isolated words through sheer effort. But, if the pace of processing is not brought up to speed, through intensive self-directed practice, reading for understanding will remain beyond grasp.

...

A well-replicated finding is that students who present with difficulties in mathematics by the end of the junior primary years show deficits in their ability to access number facts with automaticity. Such deficits stymie further development in this area, often with additional adverse consequences such as students experiencing lack of confidence, lack of enjoyment, and feelings of helplessness."

You can even see the effect of automaticity in brain scans.

At a physical level in the brain, automaticity involves developing strategic neural connections that reduce the amount of effort that the brain has to expend to activate patterns of neurons.

Researchers have observed this in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scans of participants performing tasks with and without automaticity (Shamloo & Helie, 2016).

When a participant is at wakeful rest, not focusing on a task that demands their attention, there is a baseline level of activity in a network of connected regions known as the default mode network (DMN).

The DMN represents background thinking processes, and people who have developed automaticity can perform tasks without disrupting those processes:

- "The DMN is a network of connected regions that is active when participants are not engaged in an external task and inhibited when focusing on an attentionally demanding task ... at the automatic stage (unlike early stages of categorization), participants do not need to disrupt their background thinking process after stimulus presentation: Participants can continue day dreaming, and nonetheless perform the task well."

When an external task requires lots of focus, it inhibits the DMN: brain activity in the DMN is reduced because the brain has to redirect lots of effort towards supporting activity in task-specific regions.

But when the brain develops automaticity on the task, it increases connectivity between the DMN and task-specific regions, and performing the task does not inhibit the DMN as much:

- "...[S]ome DMN regions are deactivated in initial training but not after automaticity has developed. There is also a significant decrease in DMN deactivation after extensive practice.

...

The results show increased functional connectivity with both DMN and non-DMN regions after the development of automaticity, and a decrease in functional connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and ventromedial orbitofrontal cortex. Together, these results further support the hypothesis of a strategy shift in automatic categorization and bridge the cognitive and neuroscientific conceptions of automaticity in showing that the reduced need for cognitive resources in automatic processing is accompanied by a disinhibition of the DMN and stronger functional connectivity between DMN and task-related brain regions."

In other words, automaticity is achieved by the formation of neural connections that promote more efficient neural processing, and the end result is that those connections reduce the amount of effort that the brain has to expend to do the task, thereby freeing up the brain to simultaneously allocate more effort to background thinking processes.

Now, it’s important to realize that automaticity goes beyond simple familiarity.

If you truly “know” something, then you should be able to access and leverage that information both quickly and accurately.

If you can’t, then you’re just “familiar” with it.

And when learning hierarchical bodies of knowledge – whether it be math, chess, a sport, or an instrument – it’s important to truly know things, not just be familiar with them.

Why?

Because you can’t build on familiarity. That’s what the term “shaky foundations” refers to. You can only build on a solid foundation of knowledge.

You need to learn things so well that you effectively turn your long-term memory into an extension of your working memory.

That’s how you break free from the narrow limitations of working memory.

It’s kind of like how in software, you can make a little processing power go a long way if you get the caching right.

he natural follow-up question is “how do you develop your long-term memory to the point of automaticity,” and the answer is retrieval practice (spaced, interleaved retrieval practice to be precise).

Further Reading: Retrieval Practice is F*cking Obvious

References

Brown, J. (1958). Some tests of the decay theory of immediate memory. Quarterly journal of experimental psychology, 10(1), 12-21.

Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and brain sciences, 24(1), 87-114.

D’Esposito, M. (2007). From cognitive to neural models of working memory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 362(1481), 761-772.

Hattie, J., & Yates, G. C. (2013). Visible learning and the science of how we learn. Routledge.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological review, 63(2), 81.

Roth, J. K., & Courtney, S. M. (2007). Neural system for updating object working memory from different sources: sensory stimuli or long-term memory. Neuroimage, 38(3), 617-630.

Shamloo, F., & Helie, S. (2016). Changes in default mode network as automaticity develops in a categorization task. Behavioural Brain Research, 313, 324-333.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P. L., Kalyuga, S., & Chandler, P. (2003). The expertise reversal effect. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 23-31.

Wright, R. E. (1981). Aging, divided attention, and processing capacity. Journal of Gerontology, 36(5), 605-614.

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.