Learning Loss, Grade Inflation, and Radical Constructivism

The only way to argue against the existence of learning loss and grade inflation is to argue against the very idea of measuring learning objectively (i.e., radical constructivism).

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.

It’s common for students to pass courses despite severely lacking knowledge of the content.

Why? Well, this is the obvious outcome if you look at the incentives.

Teachers typically do not face penalties for allowing students to pass courses despite severely lacking knowledge of the content.

Teachers are given no financial incentive for working hard to remedy these kinds of problematic situations that are created by other teachers.

What other outcome could you possibly expect?

Learning Loss and Grade Inflation During the COVID-19 Pandemic

What’s that? “Proof by incentives” isn’t mathematically rigorous? ;)

Then let’s take a look at some cold, hard empirical data: the co-occurrence of extreme learning loss and extreme grade inflation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

First of all, let me say that it’s hard to overstate the magnitude of that learning loss.

In fact, researchers found that that the learning loss experienced by students during COVID-19 was even more extreme than that experienced by evacuees during Hurricane Katrina, one of the deadliest hurricanes to hit the United States.

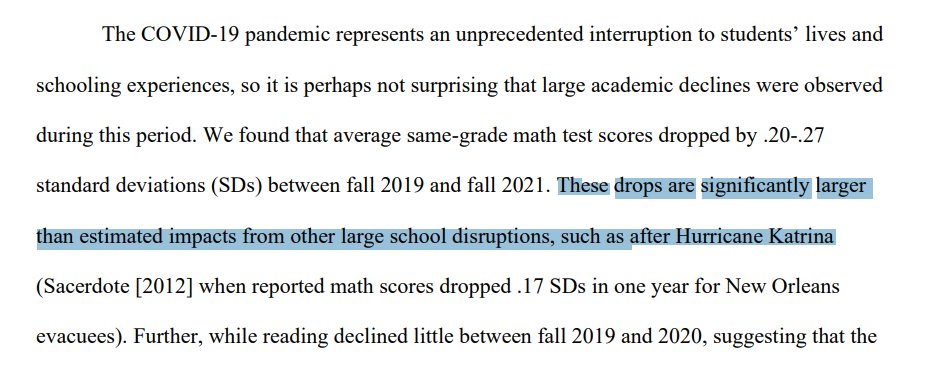

Here’s the direct quote from Test Score Patterns Across Three COVID-19-impacted School Years (Kuhfeld, Soland, & Lewis, 2022):

- "Using test scores from 5.4 million U.S. students in grades 3-8, we tracked changes in math and reading achievement across the first two years of the pandemic. Average fall 2021 math test scores in grades 3-8 were .20-27 standard deviations (SDs) lower relative to same-grade peers in fall 2019 … These drops are significantly larger than estimated impacts from other large school disruptions, such as after Hurricane Katrina (Sacerdote [2012] when reported math scores dropped .17 SDs in one year for New Orleans evacuees)."

Based on the magnitude of this learning loss, one would reasonably expect student grades to have dropped during the pandemic.

But instead, the opposite happened: grades skyrocketed and remained elevated even after most schools returned to normal in-person instruction after the pandemic.

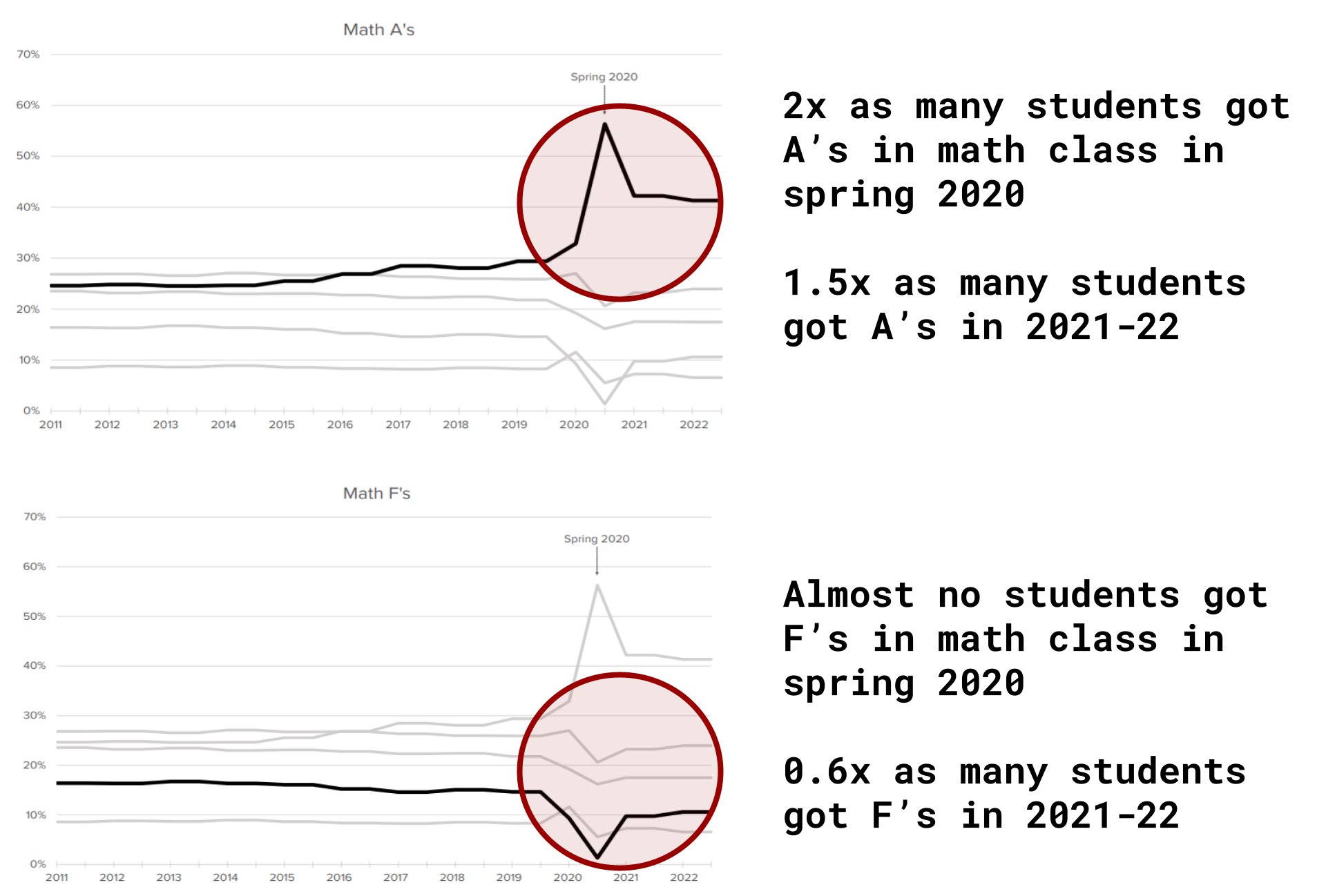

As researchers discovered when analyzing educational data from the state of Washington:

- "...[A]lmost no students received an F grade in the spring of 2020. The share of F grades dropped from … 9.3% to 1.4% in math courses ... between the fall and spring semesters of 2020. The distribution of grades higher than F mostly increased for A grades, with the share of A’s jumping from 32.9% to 56.3% in math ... The average GPA in math jumped from 2.6 to 3.2 ... The figures also suggest that English and science grades largely returned to pre-pandemic levels by 2021-22, but math grades did not. Indeed, the math GPA in 2021-22 was 2.7, 0.4 points higher than it was in 2018-19."

This quote is from Course Grades as a Signal of Student Achievement: Evidence on Grade Inflation Before and After COVID-19 (Goldhaber & Young, 2023)

The graphs in that study really drive the point home:

Note: I don't mean to suggest that the learning loss is necessarily the fault of the teacher. I personally taught classes at a public school during the pandemic had a number of disengaged students.

The point of this post is just to highlight that grades stopped representing mastery of course material, which is a big issue. Again, not necessarily the fault of the teacher: I know various pressures/policies sometimes limit or effectively remove the teacher's choice in the matter of what grades to assign.

Personally, I remember giving a student an F because they didn't do any homework, only took one exam (they got a 20%, whereas the rest of the class averaged over 80%), and showed up to maybe 3 or 4 classes the whole semester. But that grade got post-processed into a C due to some school or state policies.

Why Grade Inflation is a Problem

In short, parents might think that an “A” indicates mastery of grade-level standards, but that’s no longer the case.

If a student’s school says that they’re doing fine in math, then it does not automatically follow that the student is keeping college and career doors open that depend on mathematical proficiency.

Different schools sometimes have their own interpretations of what it means for their students to be doing fine in math, and that doesn’t always match up with grade-level standards, much less what is expected by colleges and careers.

Grade inflation is a problem because it sets students up for failure later in life when it matters most.

Every year, countless first-year college students decide to major in aerospace engineering or astrophysics or some other super-cool-sounding subject, only to have that dream crushed when they realize they can’t even pass an entry-level math course like Calc II (not even with the help of a tutor).

These problems can be remedied when students are young, before their knowledge deficits grow too large – but problems can only be fixed after they are detected, and grades are no longer a reliable tool for detecting these problems.

Brushing the Problem Under the Rug

Okay, so now that we’ve established a problem, what are we going to do about it?

Well, if you ask an organization called TODOS –

which is a member of the Conference Board of the Mathematical Sciences (CBMS), meaning that it is recognized by the International Mathematics Union (IMU) as one of the 19 national mathematical societies for the USA (for reference: the IMU awards the Fields Medal, considered to be the mathematical equivalent of the Nobel Prize) –

what we should do is… (drumroll please)

…pretend the problem does not exist.

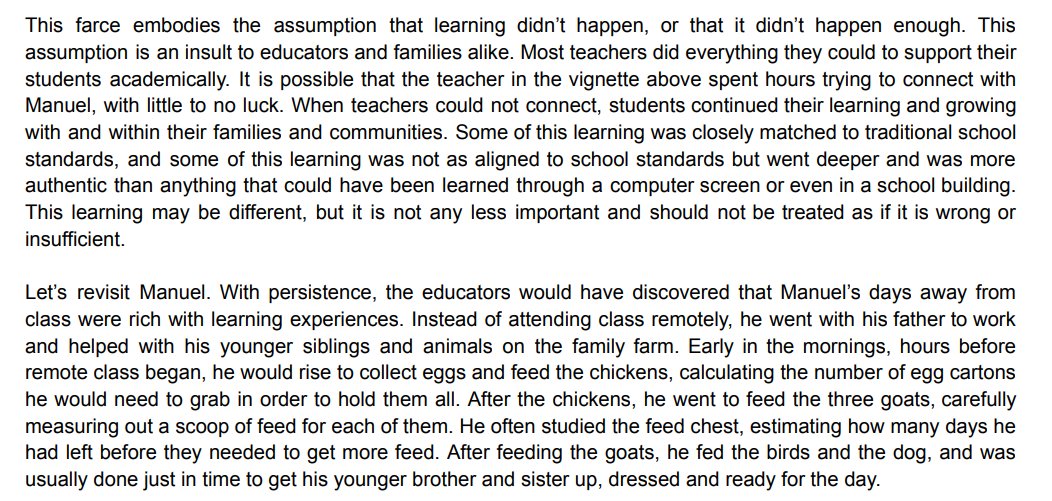

Yeah, I’m not kidding. Check out this document that TODOS circulated among educators during the 2021-22 school year: Where Is Manuel? A Rejection of ‘Learning Loss’

This document – in a refusal to accept the reality that some demographics were more affected by pandemic-induced learning losses than others – outright rejects the idea that learning loss occurred during the pandemic.

It’s one of those things that you just have to read. Here’s an amusing snippet – but seriously, the whole thing is only 5 pages and it’s super entertaining, so just look it over.

(How did I learn about this document? I was personally teaching during the pandemic and an admin emailed it to me and other teachers as a “helpful resource.”)

TODOS has released numerous other documents espousing similar viewpoints.

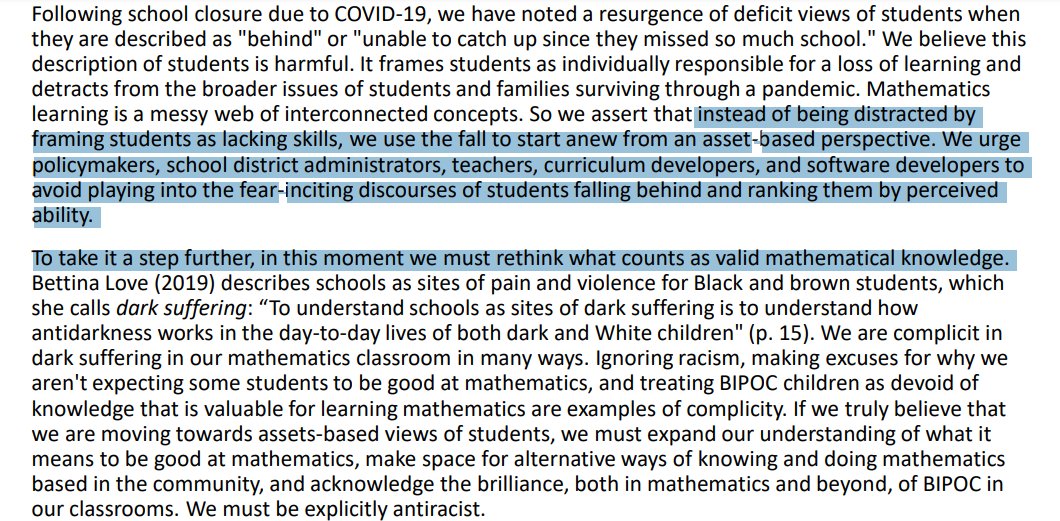

For instance, in The Mo(ve)ment to Prioritize Antiracist Mathematics: Planning for This and Every School Year (2020), released shortly before Where is Manuel, TODOS stated the following:

- "Mathematics learning is a messy web of interconnected concepts. So we assert that instead of being distracted by framing students as lacking skills, we use the fall to start anew from an asset-based perspective. We urge policymakers, school district administrators, teachers, curriculum developers, and software developers to avoid playing into the fear-inciting discourses of students falling behind and ranking them by perceived ability.

...

To take it a step further, in this moment we must rethink what counts as valid mathematical knowledge. ... [W]e must expand our understanding of what it means to be good at mathematics, make space for alternative ways of knowing and doing mathematics based in the community ..."

Fine, so, TODOS is crazy. But it’s just them, right? Well…

Check out this joint position statement between TODOS and the National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics (NCSM) from 2016:

- "...[Deficit views of historically marginalized children can arise from] the continuous labeling of children’s readiness to learn mathematics via standardized tests and other institutional tools that position and sanction specific forms of mathematics knowledge.

...

Second, deficit thinking implies that students 'lack' knowledge and experiences expected by the dominant group. Deficit thinking ignores, dismisses, or casts as barriers mathematical knowledge and experiences children engage with outside of school every day. A social justice approach to mathematics education assumes students bring knowledge and experiences from their homes and communities that can be leveraged as resources for mathematics teaching and learning"

Radical Constructivism

Okay, let’s regroup. What we’re seeing is this: the only way to argue against the existence of learning loss and grade inflation is to argue against the very idea of measuring learning objectively.

As prominent psychologists John Anderson, Lynne Reder, and Herbert Simon describe, this is indeed a tenet of an educational philosophy known as “radical constructivism”:

- "The denial of the possibility of objective evaluation is perhaps the most radical and far-reaching of the constructivist claims. … D. Charney documents that empiricism has become a four-letter word in deconstructionist writings. D. H. Jonassen describes the issue from the perspective of a radical constructivist:

‘If you believe, as radical constructivists do, that no objective reality is uniformly interpretable by all learners, then assessing the acquisition of such a reality is not possible.’"

That’s a quote from their paper Radical Constructivism and Cognitive Psychology (1998).

But even better, take it from Ernst von Glasersfeld himself, widely regarded as the philosopher who first formulated radical constructivism:

- "Radical constructivism, thus, is radical because it breaks with convention and develops a theory of knowledge in which knowledge does not reflect an ‘objective’ ontological reality, but exclusively an ordering and organization of a world constituted by our experience."

This quote is from von Glasersfeld’s An Introduction to Radical Constructivism (1984).

To concretely understand the radical constructivist position in the context of grade inflation, think about it like this.

In the absence of accountability and incentives, public spaces will become filled with trash.

Logically, the existence of excessive trash in a public space provides an argument for increasing accountability and incentives surrounding littering and janitorial work.

However, a radical constructivist will resist this conclusion on the grounds that “one person’s trash is another person’s treasure” and therefore it is impossible to objectively measure the amount of trash on the ground.

Of course, this counterargument is ridiculous and nobody would actually espouse it in the context of trash. People who enter a space can see, and agree, about how much trash is on the ground.

However, the counterargument persists in the context of education because “seeing the trash for oneself” often requires expertise in the subject matter – which most people do not have, especially in the context of mathematics.

And even those who do see the trash often turn a blind eye to it out of convenience because they don’t want to put in the extra effort to fix the situation, especially when their efforts will be met with griping from others who do not see the trash.

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.