Optimized, Individualized Spaced Repetition in Hierarchical Knowledge Structures

Spaced repetition is complicated in hierarchical bodies of knowledge, like mathematics, because repetitions on advanced topics should "trickle down" to update the repetition schedules of simpler topics that are implicitly practiced (while being discounted appropriately since these repetitions are often too early to count for full credit towards the next repetition). However, I developed a model of Fractional Implicit Repetition (FIRe) that not only accounts for implicit "trickle-down" repetitions but also minimizes the number of reviews by choosing reviews whose implicit repetitions "knock out" other due reviews (like dominos), and calibrates the speed of the spaced repetition process to each individual student on each individual topic (student ability and topic difficulty are competing factors).

This post is part of the book The Math Academy Way (Working Draft, Oct 2023). Suggested citation: Skycak, J., advised by Roberts, J. (2023). Optimized, Individualized Spaced Repetition in Hierarchical Knowledge Structures. In The Math Academy Way (Working Draft, Oct 2023). https://justinmath.com/individualized-spaced-repetition-in-hierarchical-knowledge-structures/

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.

To my best knowledge, the current literature on mathematical models for determining optimal review spacing is limited to the setting of independent flashcard-like tasks. Many subjects, in contrast, are highly connected bodies of “problem-solving” knowledge.

How do you leverage the spacing effect (i.e., perform spaced repetition) in a highly connected body of problem-solving knowledge? Initially, it might seem like an easy adjustment to a typical Anki flashcard deck:

- On one hand, it's straightforward to replace simple-recall flashards with problem-solving experiences: instead of using the same question prompt and solution for every instance of the card, put the name of a topic on the card and then pick a random problem from a pool of problems on that topic. You "recall the card correctly" if you solve that randomly-picked problem correctly.

- It's also straightforward to carry out this process while respecting prerequisite relationships: simply, don't introduce a new topic until you've successfully learned all of its prerequisites. (Before you actually introduce the topic into your spaced repetition deck, you also need to complete a lesson on the new topic where you -- with plenty of guidance and scaffolding -- actively learn and demonstrate your knowledge of the new problem-solving techniques being learned.)

HOWEVER, the subtle devil in the details is that hierarchical structure introduces significant modeling complexities when updating repetition schedules: for instance, repetitions on advanced topics should “trickle down” to update the repetition schedules of simpler topics that are implicitly practiced (while being discounted appropriately since these repetitions are often too early to count for full credit towards the next repetition).

To overcome this hurdle at Math Academy, I developed a model of Fractional Implicit Repetition (FIRe) that not only accounts for implicit “trickle-down” repetitions but also

- minimizes the number of reviews by choosing reviews (and new lessons) whose implicit repetitions "knock out" other due reviews like dominos, and

- calibrates the spaced repetition process to each individual student on each individual topic (student ability and topic difficulty are competing factors -- high student ability speeds up the overall student-topic learning speed, while high topic difficulty slows it down).

This model was the product of years of intense R&D (from 2019-22). While the specific implementation is proprietary, I can talk about the high-level ideas here. The essential components have become fairly stable by now (though I do continue refining the model each year).

Repetition Compression

A common criticism of spaced repetition is that it requires an overwhelming number of reviews. While this can be true if spaced repetition is used to learn unrelated flashcards, there is something special about the subject of mathematics that can be used to avoid this issue.

Unlike independent flashcards, mathematics is a hierarchical and highly connected body of knowledge. Whenever a student solves an advanced mathematical problem, there are many simpler mathematical skills that they practice implicitly. In other words, in mathematics, advanced skills tend to encompass many simpler skills.

As a result, whenever a student has due reviews, they can typically be compressed into a much smaller set of learning tasks that implicitly covers (i.e. provides repetitions on) all of the due reviews. I call this process repetition compression.

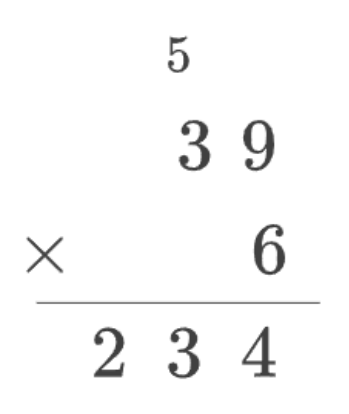

To illustrate, consider the following multiplication problem, in which we multiply the two-digit number 39 by the one-digit number 6:

In order to perform the multiplication above, we have to multiply one-digit numbers and add a one-digit number to a two-digit number:

- First, we multiply 6 × 9 = 54. We carry the 5 and write the 4 at the bottom.

- Then, we multiply 6 × 3 = 18 and add 18 + 5 = 23. We write 23 at the bottom.

In other words, Multiplying a Two-Digit Number by a One-Digit Number encompasses Multiplying One-Digit Numbers and Adding a One-Digit Number to a Two-Digit Number.

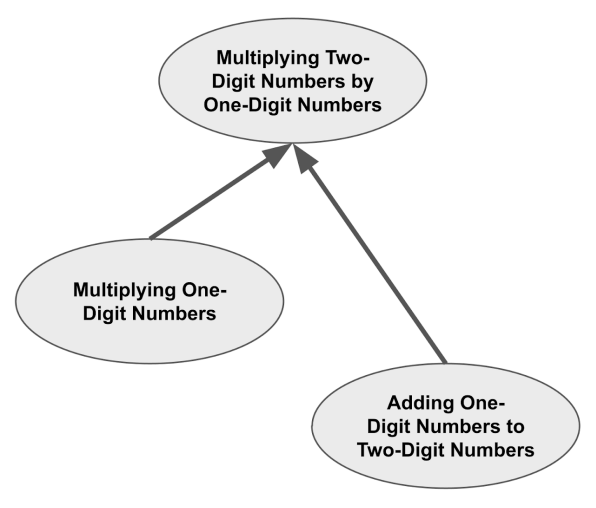

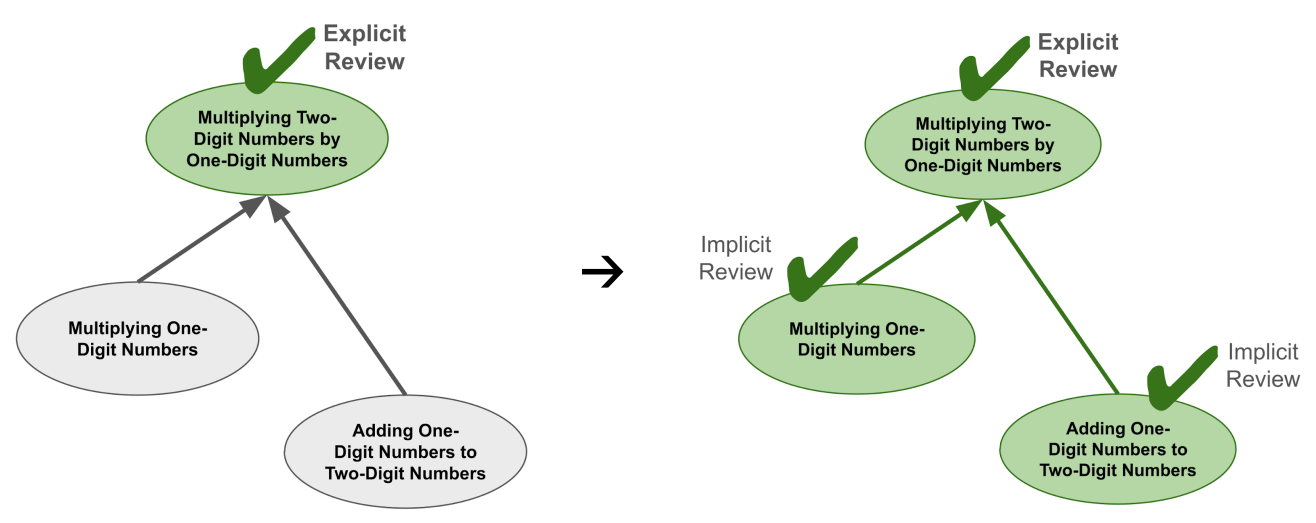

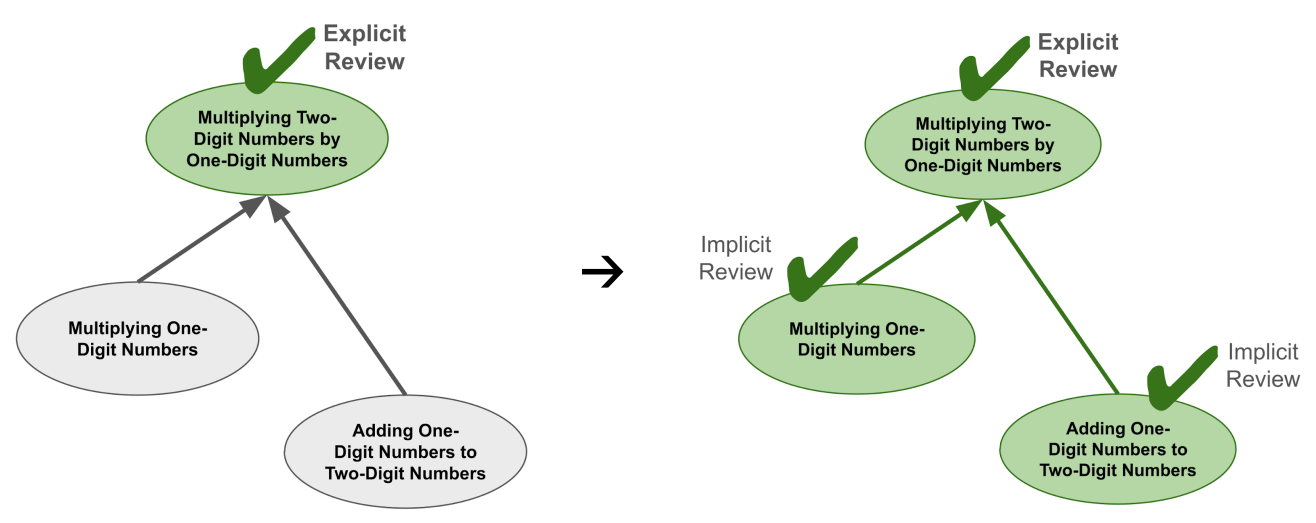

We can visualize this using an encompassing graph as shown below. The encompassing graph is similar to a prerequisite graph, except the arrows indicate that a simpler topic is encompassed by a more advanced topic. (Encompassed topics are usually prerequisites, but prerequisites are often not fully encompassed.)

Now, suppose that a student is due for reviews on all three of these topics. Because of the encompassings, the only review that they will actually have to do is Multiplying a Two-Digit Number by a One-Digit Number. When they complete this review, it will implicitly provide repetitions on the topics that it encompasses because the student has effectively practiced those skills as well.

In general, the more encompassings there are, the fewer explicit reviews are actually required. And mathematics has lots of encompassings!

(Note that repetition compression extends beyond knocking out currently due reviews: once no more due reviews remain, repetition compression chooses tasks to minimize future explicit review as well by fending off upcoming reviews. It also climbs the knowledge graph evenly to maintain a broad spread of choices for future optimization.)

Learning Efficiency

In physics, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light. It is the theoretical maximum speed that any physical object can attain. A universal constant.

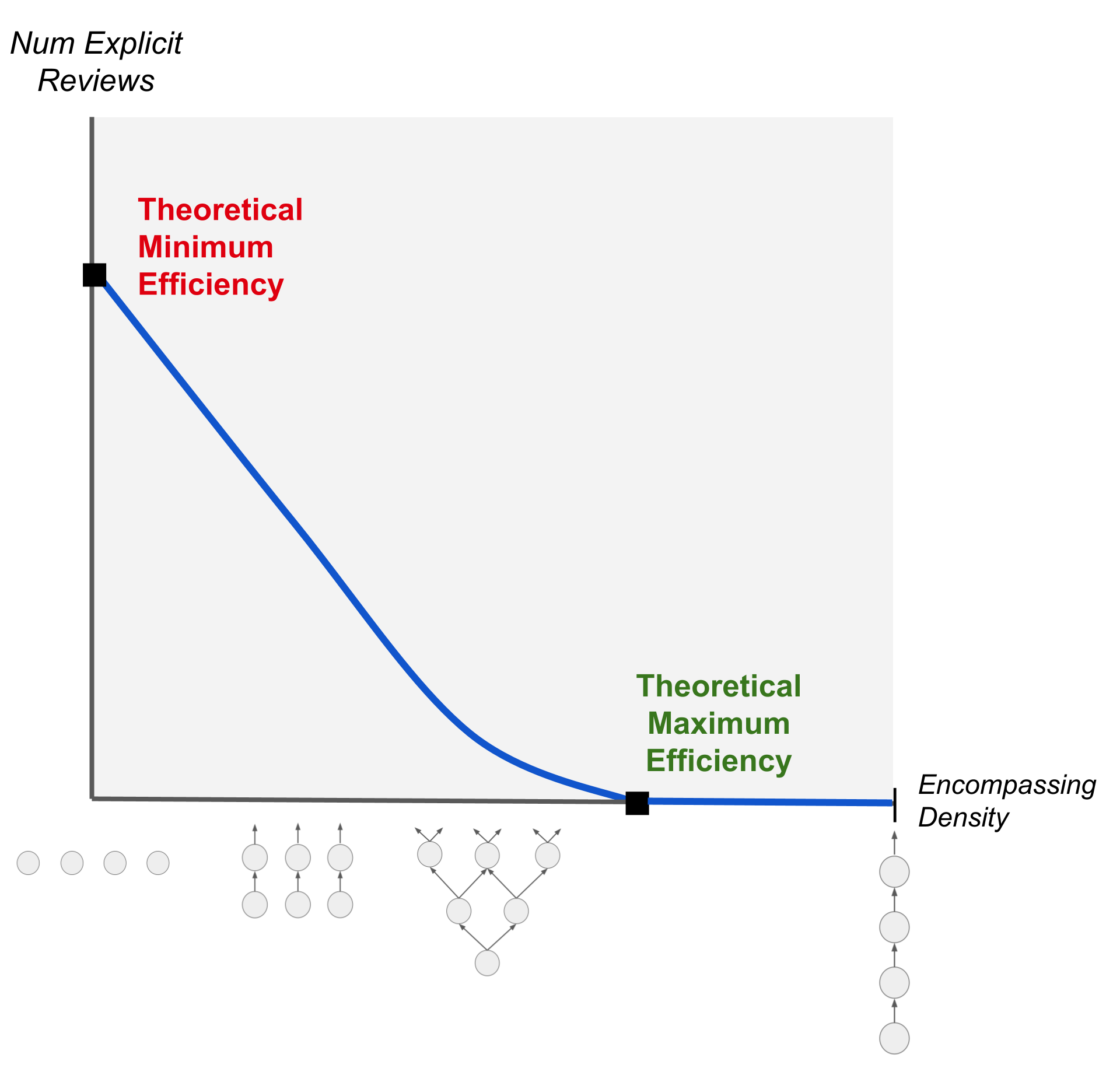

In the context of spaced repetition, there is an analogous concept: theoretical maximum learning efficiency. In theory, given a sufficiently encompassed body of knowledge, it is possible to complete all your spaced repetitions without ever having to explicitly review previously-learned material.

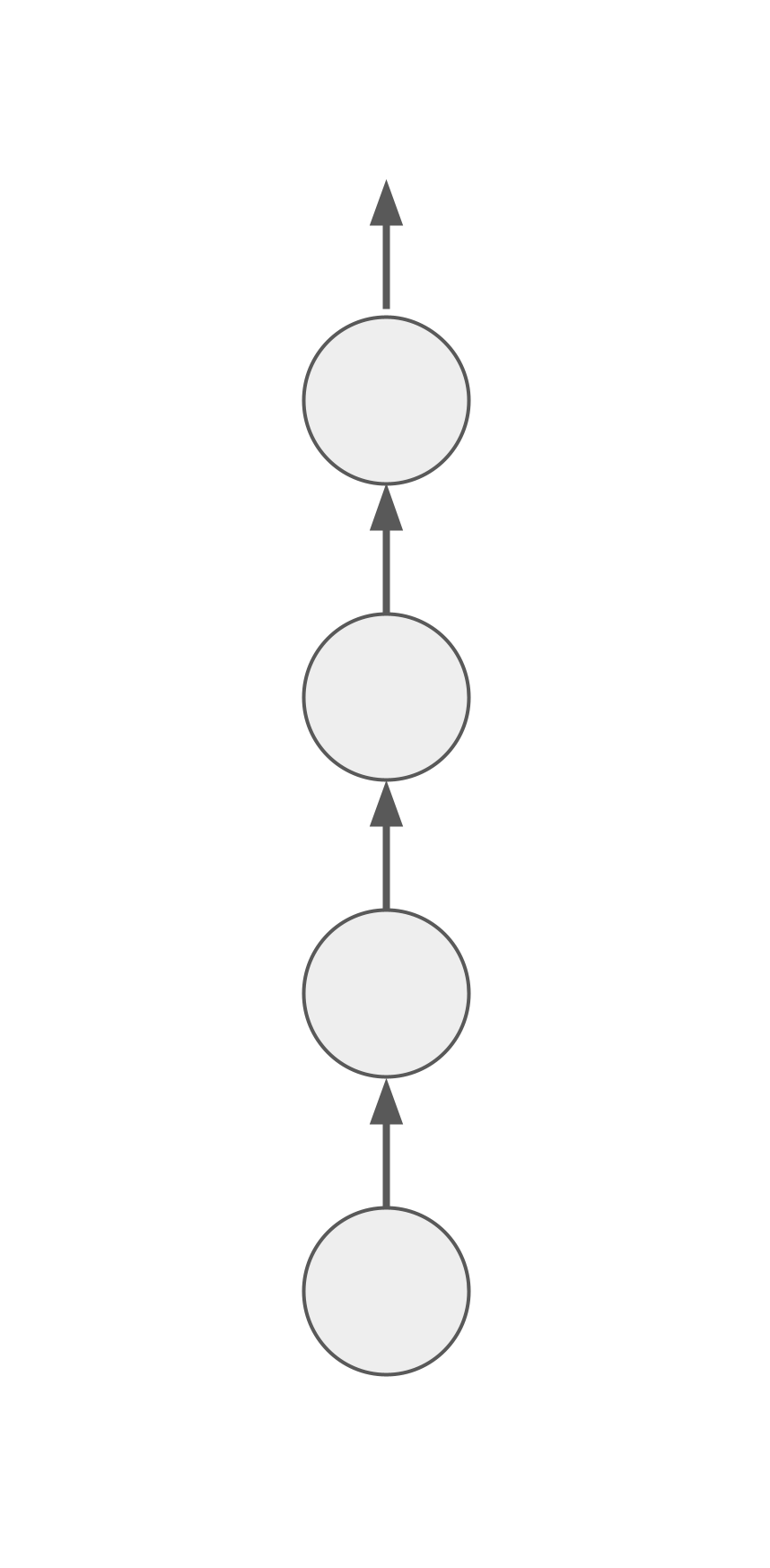

As a simple demonstration, consider a sequence of topics where the first topic is fully encompassed by the second, which is fully encompassed by the third, which is fully encompassed by the fourth, and so on.

Each time you learn the next topic, all the topics below receive full implicit repetitions. Assuming that you never run out of new topics to learn, the only reason you would ever need to do an explicit repetition is if you get stuck repeatedly attempting and failing to learn the next topic.

By contrast, there is also a concept of theoretical minimum learning efficiency. This is precisely the setting of independent flashcards – or equivalently, a set of topics without any encompassings.

In this setting, no topic can receive implicit repetitions from any other topic. Every single review must be done explicitly.

It’s important to realize that a graph does not have to be fully encompassed, or even nearly fully encompassed, for its maximum learning efficiency to approach the theoretical limit. Even if most relationships between topics are non-encompassing, a considerable minority of encompassings goes a long way.

Fractional Implicit Repetition (FIRe)

Now that we’ve introduced the idea of repetition compression, let’s extend to the general idea of fractional implicit repetitions (FIRe) flowing through an encompassing graph.

FIRe generalizes spaced repetition to hierarchical bodies of knowledge where

- repetitions on advanced topics "trickle down" implicitly to simpler topics through encompassing relationships, and

- simpler topics receiving lots of implicit repetitions discount the repetitions appropriately (since they are often too early to count for full credit towards the next repetition).

Concrete Example

As a concrete example, recall that Multiplying a Two-Digit Number by a One-Digit Number encompasses Multiplying One-Digit Numbers and Adding a One-Digit Number to a Two-Digit Number.

If you pass a review on Multiplying a Two-Digit Number by a One-Digit Number, then the repetition will also flow backward to reward Multiplying One-Digit Numbers and Adding a One-Digit Number to a Two-Digit Number because you’ve just shown evidence that you still know how to perform these skills.

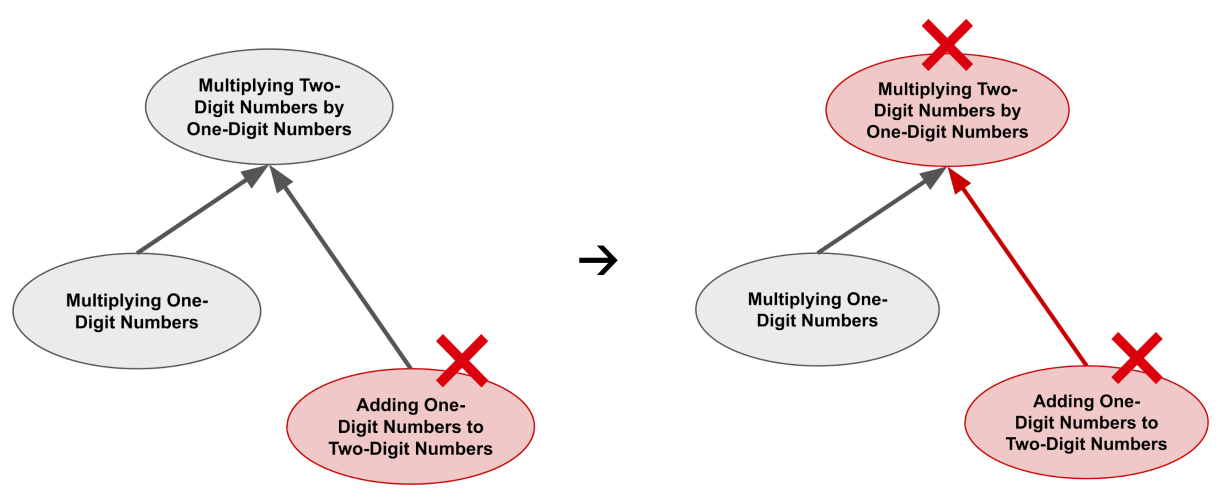

On the other hand, if you fail a repetition on Adding a One-Digit Number to a Two-Digit Number, then the failed repetition will also flow forward to penalize Multiplying a Two-Digit Number by a One-Digit Number. If you can’t add a one-digit number to a two-digit number, then there’s no way you’re able to multiply a two-digit number by a one-digit number. The same thing happens if you fail a repetition on Multiplying One-Digit Numbers.

Visualizing Repetition Flow

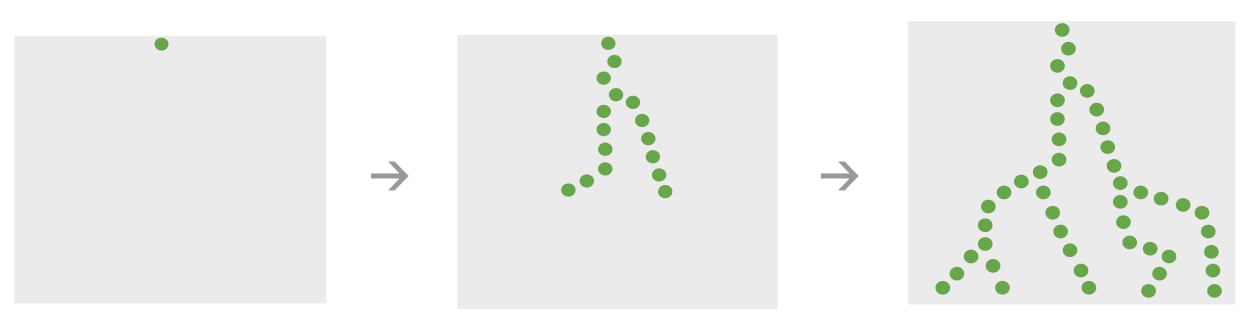

Note that repetition flows can extend many layers deep – not just to directly encompassed topics, but also to “second-order” topics that are encompassed by the encompassed topics, and then to third-order topics that are encompassed by second-order topics, and so on.

Visually, credit travels downwards through the knowledge graph like lightning bolts.

Penalties travel upwards through the knowledge graph like growing trees.

Partial Encompassings

FIRe also naturally handles cases of partial encompassings, in which only some part of a simpler topic is practiced implicitly in an advanced topic. This occurs more frequently in higher-level math.

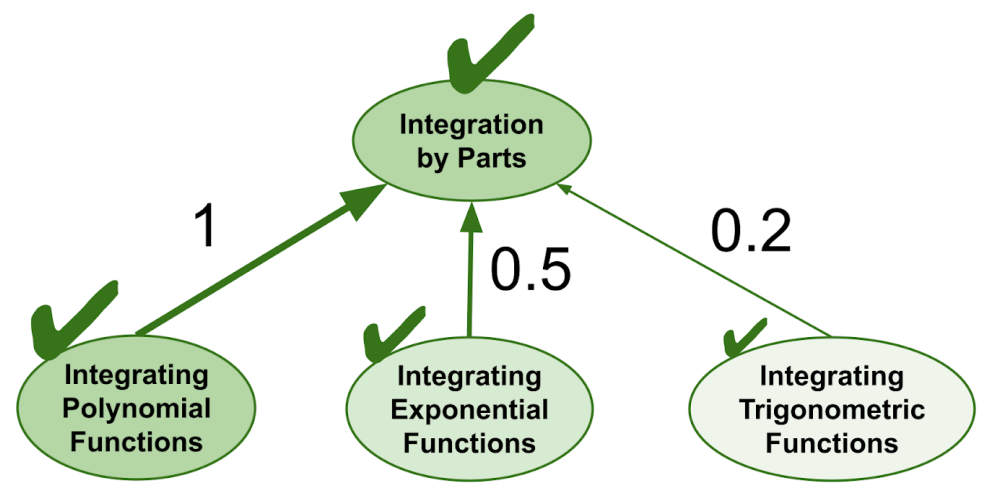

For instance, in calculus, advanced integration techniques like integration by parts require you to calculate integrals of a variety of mathematical functions such as polynomials, exponentials, and trigonometric functions. But some of those functions might only appear in a portion of the integration by parts problems. So, if you complete a repetition on integration by parts, you should only receive a fraction of a repetition towards each partially-encompassed topic.

In the diagram below, we label encompassings with numerical weights that represent what fraction of each simpler topic is practiced during the more advanced topic. You can loosely interpret each weight as representing the probability that a random problem from the advanced topic encompasses a random problem from the simpler topic.

FIRe extends repetition flows many layers deep through fractional encompassings as well. The end result is that repetitions

- travel unhindered along a "trunk" of full encompassings, and

- fade off along partial encompassings branching outwards from the trunk.

Setting Encompassing Weights Manually

Because encompassing weights are set manually, it is not feasible to set an explicit weight between every pair of topics in the graph. We have thousands of topics, so the full pairwise weight matrix would contain tens of millions of entries. How do we set all those weights?

It turns out that it is not actually necessary to explicitly set every weight in the matrix. It suffices to set only the weights for topic pairs where

- the weight has a nontrivial value,

- the weight cannot otherwise be inferred using repetition flow, and

- the distance between the topics in the prerequisite graph is low,

and assume that all other weights not computed implicitly during repetition flow are zero. The reasoning behind these conditions is as follows:

- The magnitude of the weight represents the magnitude of the implicit repetition credit. In order for an implicit repetition to make an impact on staving off explicit reviews, it has to be associated with a nontrivial amount of credit.

- If repetition flow can infer a weight, then nothing will change if the weight is set manually (unless the manually-set weight is being used to correct a value that would otherwise be inferred by repetition flow).

- If two topics are far apart in the prerequisite graph, then their weight will not make much of an impact on staving off reviews, even if it is a full encompassing. In that case, by the time the student reaches the more advanced topic, they will already have done most of their explicit reviews on the simpler topic.

Conveniently, the weights that satisfy the above conditions tend to be those along direct and key prerequisite edges, the number of which scales linearly with the number of topics. This makes it feasible to set encompassing weights manually: one weight for each direct or key prerequisite

Note that it is not unusual to find direct and key prerequisite edges with a weight as low as zero. This can happen when a topic requires some amount of conceptual familiarity with the prerequisite, but does not require the student to actually have mastered the prerequisite to the point of being able to solve problems in the prerequisite topic.

Calibrating to Individual Students and Topics

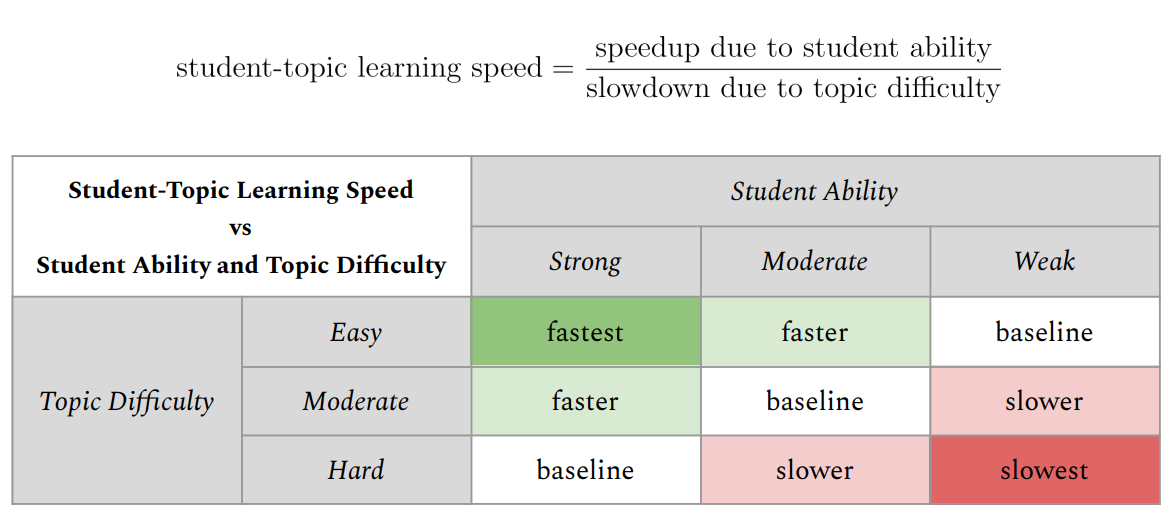

The speed at which students learn (and remember what they’ve learned) varies from student to student. It has been shown that some students learn faster and remember longer, while other students learn slower and forget more quickly (e.g., Kyllonen & Tirre, 1988; Zerr et al., 2018; McDermott & Zerr, 2019). Similarly, learning speed also varies across topics: easier topics are learned faster and remembered longer, while harder topics take longer to learn and are forgotten more quickly.

So, for each student, each topic has a learning speed that depends on the student’s ability and the topic’s difficulty. Student ability and topic difficulty are competing factors – high student ability speeds up the overall student-topic learning speed, while high topic difficulty slows it down. In this view, a student-topic learning speed can be measured as a ratio between

- the speedup due to student ability, and

- the slowdown due to topic difficulty.

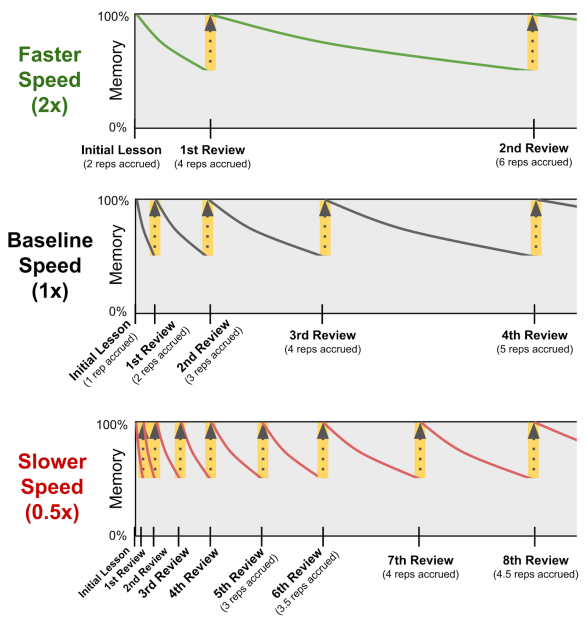

Student-topic learning speeds are used to adjust the speed of the spaced review process.

- For instance, if a student does a review on a topic for which their learning speed is 2x, then that review counts as being worth 2 spaced repetitions.

- Likewise, if a student does a review on a topic for which their learning speed is 0.5x, then that review counts as being worth 0.5 spaced repetitions.

Student-topic learning speeds are also considered within the fractional implicit repetition algorithm. Weaker students often have trouble absorbing implicit repetitions on difficult topics – they have a harder time generalizing that “what I learned earlier is a special case (or component) of what I’m learning now.”

So, whenever a topic’s spaced repetition process is being slowed down (i.e. whenever the student-topic learning speed is less than 1), it’s best to discard all incoming implicit repetition credit and instead force explicit reviews. In other words, the topic will not receive any implicit repetition credit that would normally “trickle down” from more advanced topics that encompass it.

It makes sense for the decision of whether or not to force explicit reviews to be based on the student-topic learning speed because when a topic’s spaced repetition process is being slowed down, it indicates that the topic is considered rather difficult relative to the student’s ability.

Lastly, it’s important to realize that while there are a number of factors that could affect a student’s learning speed, such as their aptitude, forgetting rate, level of interest/motivation, or how tired or distracted they typically are while working on learning tasks – these factors are ultimately only as relevant as their effects on the student’s observed performance. Consequently, each student’s individual learning curve can be calibrated appropriately on the sole basis of their observed performance.

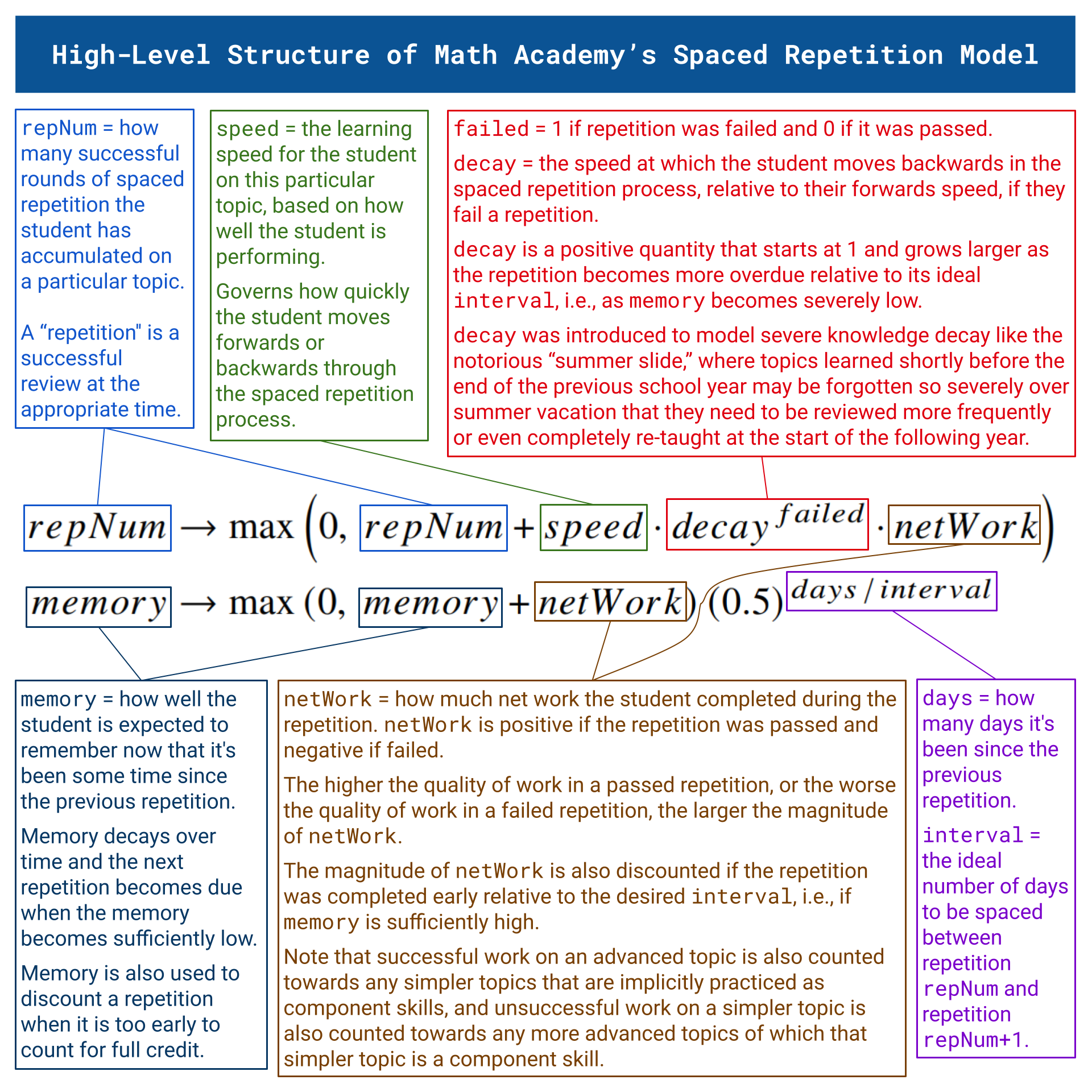

High-Level Structure of Spaced Repetition Model

At a high level, the structure of my spaced repetition model can be summarized as follows:

- $repNum=$ how many successful rounds of spaced repetition the student has accumulated on a particular topic.

In following definitions, a "repetition" is a successful review at the appropriate time. - $days=$ how many days it's been since the previous repetition.

- $interval=$ the ideal number of days to be spaced between repetition $repNum$ and repetition $repNum+1.$

- $memory=$ how well the student is expected to remember now that it's been some time since the previous repetition. Memory decays over time and the next repetition becomes due when the memory becomes sufficiently low. Memory is also used to discount a repetition when it is too early to count for full credit.

- $speed=$ the learning speed for the student on this particular topic, based on how well the student is performing. Governs how quickly the student moves forwards or backwards through the spaced repetition process.

- $failed=1$ if repetition was failed and $0$ if it was passed.

- $rawDelta=$ how much raw spaced repetition credit the student earned during the repetition, ignoring speed and decay. $rawDelta$ is positive if the repetition was passed and negative if failed.

The higher the quality of work in a passed repetition, or the worse the quality of work in a failed repetition, the larger the magnitude of $rawDelta.$

The magnitude of $rawDelta$ is also discounted if the repetition was completed early relative to the desired $interval,$ i.e., if $memory$ is sufficiently high.

Note that successful work (positive credit) on an advanced topic is also counted towards any simpler topics that are implicitly practiced as component skills, and unsuccessful work (negative credit) on a simpler topic is also counted towards any more advanced topics of which that simpler topic is a component skill. - $decay=$ the speed at which the student moves backwards in the spaced repetition process, relative to their forwards speed, if they fail a repetition.

$decay$ is a positive quantity that starts at $1$ and grows larger as the repetition becomes more overdue relative to its ideal $interval,$ i.e., as $memory$ becomes severely low.

$decay$ was introduced to model severe knowledge decay like the notorious "summer slide," where topics learned shortly before the end of the previous school year may be forgotten so severely over summer vacation that they need to be reviewed more frequently or even completely re-taught at the start of the following year.

Some Clarifications in Response to Follow-Up Questions

I received some great follow-up questions about this post after it gained some traction on HackerNews (July 2024). Below are some points I’d like to clarify about the above approach.

The learner is first introduced to the topics through mastery learning, i.e., they do not learn a new topic until they have already seen and mastered the prerequisite topics. It’s only in the review phase when we do all the stuff involving “knocking out” repetitions implicitly.

Students are not simply memorizing answers. The questions are different every time, testing the same concept / process but not allowing students to simply memorize the answer.

Is math uniquely suited for this kind of strategy, or does it translate to learning concepts in other domains too?

The power of this strategy comes from leveraging the hierarchical, highly-encompassed nature of the structure of mathematical knowledge. The strategy should carry over to any other knowledge domain that has a serious density of encompassings. But if a knowledge domain lacks a serious density of encompassings, there’s just a hard limit to how much review you can “knock out” implicitly.

What happens if a student is shown a topic but doesn’t remember one of the necessary prerequisites?

There are both theoretical and practical safeguards. For the sake of explanation, let’s say topic A is a prerequisite for topic B.

Theoretical Safeguard

If you are at risk of forgetting A in the near future, then you’ll have a repetition due on A right now, which means you’re going to review it right now (by “knocking it out” with some more advanced topic if possible, but if that’s not possible, then we’ll give you an explicit review of B itself).

In general, if a repetition is due, we’re not going to wait for an “implicit knock-out” opportunity to open up and let you forget it while we wait. We’ll just say “okay, guess we can’t knock this one out implicitly right now” and give you an explicit review.

Practical Safeguard

Suppose that for whatever reason, the review timing is a little miscalibrated and a student ends up having forgotten more of A than we’d like when they’re shown B. Even then, they haven’t forgotten A completely, and they can refresh on A pretty easily. Often, that refresher is within B itself: for instance, if you’re learning to solve equations of the form $ax+b=cx+d,$ then the explanation is going to include a thorough reminder of how to solve $ax+b=c.$

And even in other cases where that reminder might not be as thorough, if you’re too fuzzy on A to follow the explanation in B, then you can just refer back to the content where you learned A and freshen up: “Huh, that thing in B is familiar but it involves A and I forgot how you do some part of A… okay, look back at A’s lesson… ah yeah, that’s right, that’s how you do it. Okay, back to B.” And then the act of solving problems in B solidifies your refreshed memory on A.

In the worst-case scenario, if a student manages to completely forget A to the point where they are unable to freshen up on it by looking at the reference material, then we also have a remediation process in place to explicitly given them extra practice on A. In B’s lesson, we keep track of where prerequisites are used, so if a student “plateaus” on the lesson for B (i.e., they fail the lesson twice in a row without getting any further the second time), then we trigger remedial learning tasks on the prerequisites where the student got stuck.

But isn’t it possible that you might not necessarily activate a parent concept by answering a child concept, even though they form a hierarchy?

This is where it’s really important to distinguish between “prerequisite” vs “encompassing.” Admittedly I probably should have explained this better in the article, but yes, prerequisites are not necessarily activated. If you do FIRe on a prerequisite graph, pretending prerequisites are the same as encompassings, then you’re going to get a lot of incorrect repetition credit trickling down.

We actually faced that issue early on, and the solution was that I just had to go through and manually construct an “encompassing graph” by encoding my domain-expert knowledge, which was a ton of work, just like manually constructing the prerequisite graph. You can kind of think of the prerequisite graph as a “forwards” graph, showing what you’re ready to learn next, and the encompassing graph as a “backwards” graph, showing you how your work on later topics should trickle back to award credit to earlier topics.

Manually constructing the encompassing graph was a real pain in the butt and I spent lots of time just looking at topics asking myself “if a student solves problems in the ‘post’-requisite topic, does that mean we can be reasonably sure they truly know the prerequisite topic? Like, sure, it makes sense that a student needs to learn the prerequisite beforehand in order for the learning experience to be smooth, but is the prerequisite really a component skill here that we’re sure the student is practicing?” Turns out there are many cases where the answer is “no” – but there are also many cases where the answer is “yes,” and there are enough of those cases to make a huge impact on learning efficiency if you leverage them.

I still have to make updates to the encompassing graph every time we roll out a new topic, or tweak an existing topic. Having domain expertise about the knowledge represented in the graph is absolutely vital to pull this off. (In general, our curriculum director manages the prerequisite graph, and I manage the encompassing graph.)

Are there any academic results? Does this modification to SRS help? Which type of student does it help? How large is the effect if there is one?

The main idea is that this approach makes spaced repetition feasible in something like mathematics. Without this approach, spaced repetition wouldn’t even be feasible because after a short while, you’d be continually overloaded with too many reviews to really make any progress learning new material.

Moreover, in addition to making spaced repetition feasible, it minimizes the amount of review (subject to the condition that you’re getting sufficient review) which allows you to make really fast progress.

We (Math Academy) don’t have any official academic studies out at the moment, but if you want some kind of more concrete evidence of learning efficiency, you can read more online about our original in-school program in Pasadena where we have 6th graders start in Prealgebra, and then learn the entirety of high school math (Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, Precalculus) by 8th grade, and then in 8th grade they learn AP Calculus BC and take the AP exam.

The AP scores started off decent while doing manual teaching, but the year we started using our automated system (of which the SRS described here is a component), the AP Calculus BC exam scores rose, with most students passing the exam and most students who passed receiving the maximum score possible (5 out of 5). Four other students took AP Calculus BC on our system that year, unaffiliated with our Pasadena school program, completely independent of a classroom, and all but one of them scored a perfect 5 on the AP exam (the other one received a 4).

Even some seemingly impossible things started happening like some highly motivated 6th graders (who started midway through Prealgebra) completing all of what is typically high school math (Algebra I, Geometry, Algebra II, Precalculus) and starting AP Calculus BC within a single school year. Funny enough, the first time Jason & Sandy (MA founders) saw a 6th grader receiving AP Calculus BC tasks, Jason’s reaction was “WTF is happening with the model, why is this kid getting calculus tasks, he placed into Prealgebra last fall, this doesn’t make any sense,” but I looked into it only to find that it was legit – this kid completed all of high school math within a single school year.

Anyway, some links if you’re interested: mathacademy.us/press, relevant Reddit thread, story I posted on X/Twitter (and some follow-up to that story).

Again, I realize these are not official academic studies, but we’re completely overloaded in startup grind mode right now and have so many fish to fry with the product that we just don’t have the time for academic pursuits at the moment, let alone a full night’s sleep.

Is spaced repetition really infeasible without these modifications to cut down on review?

I’ve used Anki to learn and retain a lot of math. It’s not perfect, and I would love to have a DAG, but in my experience, basic topics end up being proven understood enough that they are backed off from review for a long time. So I might not be asked about a basic topic / problem for a year. This seems to prevent being overloaded with duplicate / repeat cards.

However, if I do find that I am faced with a more advanced card that I have forgotten some of the foundations on, it is frustrating to have to do that card instead of doing a series of progressive reviews upwards through the ancestors.

Of course, if I keep up with Anki every day (10-20 minutes) I don’t forget any of the foundations, but if I take 2-3 months off and come back to my deck, I can be faced with this problem and have to sometimes go manually digging for relevant background topics.

These are fair points; I guess the feasibility of spaced repetition comes down to what you consider a repetition. If you’re considering a single quick problem on a topic to be a repetition, and you don’t have too many topics, and you’re not plowing through them too quickly, then I can see it being feasible as you’re saying.

Math Academy is built with a different context in mind:

- we have tons of different topics (for instance, over 300 in our AP Calculus BC course -- and that's just one course; students who stick with us past their first course and continue taking more courses on our system can easily accumulate thousands of topics on which they need to maintain their knowledge)

- each repetition consists of multiple questions on a topic (after an initial lesson task consisting of somewhere in the ballpark of 10 questions, future repetitions are review tasks in the range of 3-5 review questions)

- students are getting through a new topic every 20 minutes or so on average (our AP Calculus BC course is estimated to take about 6000 minutes, and that includes time spent on review / quizzes / etc. Calculation: 6000 minutes / 300 topics = 20 minutes/topic)

Just some back-of-the envelope math in our context: say you learn 3 new topics per day (an hour-long session), and each review takes you about 4 questions. Then, as a rough estimate, pretty quickly you reach a point where you’ve got

- 12 review questions based on yesterday's lessons,

- + another 12 review questions on topics you reviewed for the first time last week,

- + another 12 review questions on topics you reviewed for the second time a couple weeks ago, + another 12 review questions on topics you reviewed for the third time a month ago,

- + another 12 review questions on topics you reviewed for the fourth time a couple months ago,

- ...

That’s already 60 review questions/day, already past the point where you’re spending every hour-long session entirely on review, which means that your progress grinds to a halt in terms of learning new material.

So, in our context at least, raw spaced repetition just doesn’t work out in a way that’s feasible – student will get absolutely crushed by a tsunami of review unless we unless we take measures to drastically cut down the amount of review (i.e., fractional implicit repetition + repetition compression).

I hear your point about needing some refresher if you take 2-3 months off and come back, though. Similar thing happens with Math Academy students if they take time off and come back, but the way we solve that problem is we just recommend they take a new diagnostic to refresh their knowledge profile. Basically, it just peels back their “knowledge frontier” to a point where they can pick up and continue learning smoothly with our standard approach.

(In my experience, that’s what you’d ideally do as a teacher after summer vacation – you know your students have forgotten a lot of material, so you have them take a beginning-of-the-year knowledge evaluation and go from there.)

Did you look into Bayesian Knowledge Tracing? What was your impression of it?

I think Bayesian Knowledge Tracing is a decent initial mental model for the situation. It’s the natural approach if you’re comfortable with Bayesian probability, and my first approach to our diagnostic algorithm was along those lines.

However, as it typically goes when building a model to make tons of different kinds of decisions and be robust to tons of different kinds of issues, complexity explodes and you have to find ways to reign it in. The model becomes a system and a system’s worst enemy is its own complexity.

After many cycles of reigning in the complexity I ended up moving towards less of a probabilistic approach and more of a “physical” approach where I envision every answer as a “fractional repetition” physically flowing through the knowledge graph, providing rewards or penalties to related nodes.

So far, FIRe has been great unifying approach encapsulating everything we’ve needed the model to do, and it’s super concrete/interpretable which makes it really easy to think about, troubleshoot, and build on top of.

(I don’t claim my approach is the only way to build a learning system, but I personally can’t think of any other approach I could have used to thread the needle on all the challenges that we’ve faced in the past and expect to face in the future, and it is true that most of these challenges are not actually addressed in academic papers.)

References

Kyllonen, P. C., & Tirre, W. C. (1988). Individual differences in associative learning and forgetting. Intelligence, 12(4), 393-421.

McDermott, K. B., & Zerr, C. L. (2019). Individual differences in learning efficiency. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(6), 607-613.

Zerr, C. L., Berg, J. J., Nelson, S. M., Fishell, A. K., Savalia, N. K., & McDermott, K. B. (2018). Learning efficiency: Identifying individual differences in learning rate and retention in healthy adults. Psychological science, 29(9), 1436-1450.

This post is part of the book The Math Academy Way (Working Draft, Oct 2023). Suggested citation: Skycak, J., advised by Roberts, J. (2023). Optimized, Individualized Spaced Repetition in Hierarchical Knowledge Structures. In The Math Academy Way (Working Draft, Oct 2023). https://justinmath.com/individualized-spaced-repetition-in-hierarchical-knowledge-structures/

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.