Active Learning: If You’re Active Half the Time, That’s Still Not Enough

During practice, the elite skaters were over 6 times more active than passive, while non-competitive skaters were nearly as passive as they were active.

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.

Many people know that active learning is superior to passive learning, and that deliberate practice is the most effective type of active learning.

However, many of those people still don’t understand just how much of a practice session should constitute active learning.

Even if you’re active half the time during practice, that’s still not enough to capture anywhere near the full benefits of active learning.

Don’t believe it? Let me tell you about this study on the practice habits of figure skaters: A Search for Deliberate Practice by Deakin & Cobley (2003, pp.124-136).

Deakin & Cobley studied the practice habits of figure skaters who had been practicing for a similar number of years and had achieved varying degrees of success.

A defining attribute separating the elite and non-competitive skaters was the proportion of active practice.

During practice,

- elite skaters were over 6 times more active than passive, while

- non-competitive skaters were nearly as passive as they were active.

The elite skaters spent a greater proportion of their practice time actively practicing some of the trickiest, most taxing moves (jumps & spins) –

and even when resting from those taxing activities, they were more likely to continue actively practicing less taxing movements like footwork and arm positions.

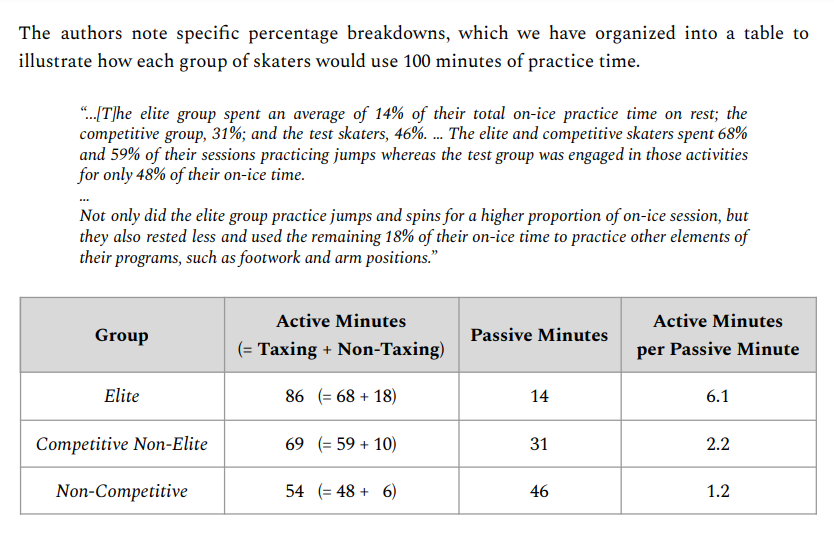

Deakin & Cobley noted specific percentage breakdowns, which I organized into a table to illustrate how each group of skaters would use 100 minutes of practice time. Below is a snippet from The Math Academy Way:

Essentially, the elite skaters were on the ice for the same amount of time as the non-competitive skaters, but during that on-ice time, the elite skaters allocated their practice time far more efficiently.

The key takeaway is that, while some amount of active learning is certainly better than no active learning…

the BEST outcomes are achieved by fully maximizing the amount of productive active learning.

Of course, some passive instruction will generally be needed to demonstrate to a learner what it is that they need to practice…

but that passive instruction should be kept to a minimum effective dose before launching into more extensive active learning.

And remember that it’s not just any type of active learning that we’re talking about. There are a million ways to do active learning wrong,

but the way to do it right is deliberate practice: mindful repetition on performance tasks just beyond the edge of one’s capabilities.

Deliberate practice is about making performance-improving adjustments on every single repetition.

Any individual adjustment is small and yields a small improvement in performance –

but when you compound these small changes over a massive number of action-feedback-adjustment cycles, you end up with massive changes and massive gains in performance.

Deliberate practice is superior to all other forms of training. That is a “solved problem” in the academic field of talent development. It might as well be a law of physics.

There is a mountain of research supporting the conclusion that the volume of accumulated deliberate practice is the single biggest factor responsible for individual differences in performance among elite performers across a wide variety of talent domains.

(The next biggest factor is genetics, and the relative contributions of deliberate practice versus genetics can vary significantly across talent domains.)

Further Reading: Chapter 10: Active Learning in The Math Academy Way.

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.